Scientists at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and Northern Illinois University (NIU) have developed a way to prevent lead from escaping damaged perovskite solar cells. This could go a long way in addressing concerns about potential lead toxicity.

Image by NREL, from Phys.org

Image by NREL, from Phys.org

The light-absorbing layer in perovskite solar cells contains a small amount of lead. Simply encapsulating solar cells does not stop lead from leaking if the device is damaged. Instead, chemical absorption may hold the key. The researchers report being able to capture more than 99.9% of the leakage.

Zhu and some of the same researchers of his current team in 2020 reported successful experiments in sequestering lead should a perovskite cell become damaged. They developed lead-absorbing films, applied them to the two sides of a cell, and then smashed them with a hammer and slashed them with a knife. The damaged cell was then immersed in water. The scientists found the films prevented more than 96% of the lead from leaking into the water.

Other researchers followed up on the lead concern and developed a resin that could be incorporated into a perovskite solar cell. But, as the NREL and NIU scientists noted, "These additional modifications could complicate the device fabrication and configuration and potentially limit device performance and scale-up."

Instead, the authors noted in the paper, a better proposition may be to develop durable and highly efficient lead-absorbing components that can be "conveniently mounted" onto the perovskite solar cell as an accessory.

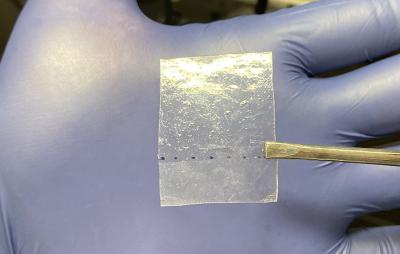

The NREL and NIU scientists believe they have found a solution in using a tape-like chemical absorption approach that can be readily installed on both sides of a perovskite solar cell. In a series of tests, the tapes captured almost all of the lead leakage without compromising the cell's performance and operation. The tapes were made of a standard solar ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) film and a pre-laminated di(2-ethylhexyl) methanediphosphonic acid layer.

After damaging the perovskite solar cells, the scientists conducted a series of tests to quantify how much lead would escape into water. In one experiment, the concentration of lead in water that fell on the damaged device averaged about 19.14 parts per million. The tape brought that figure down to 2.13 parts per billion. To put this figure in context, the Environmental Protection Agency considers water safe to drink if the lead content is less than 15 parts per billion.

"Since EVA has been extensively used as a cost-effective and durable encapsulating material for silicon-based solar panels, the integration of lead-absorbing materials with EVA provides an industrially ready and stand-alone component to facilitate the future market adoption of perovskite solar cells," Xu said.